The Nereus Program will have a presence at the International Marine Conservation Congress taking place from July 30th to August 3rd in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada.

Following the theme of “Making Science Matter” to stakeholders, policy makers, and practitioners in order for conservation efforts to be successful, the congress will revolve around specific topics related to marine conservation.

Schedule for Nereus-affiliated sessions:

Sunday, July 31, 2016

Poster Session – 17:30-19:30

Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor – “Impacts of ecotourism on conservation and resource management at local and global scales”

Abstract: Marine ecotourism can have clear conservation benefits when species become more valuable alive than dead. Such economic and ecological success has been achieved by communities around the world that benefit from species (e.g. whales, sharks, sea lions) or ecosystems (e.g. reefs, mangroves). The role of ecotourism in prompting international conservation is less clear, but there is strong supporting evidence of its influence at these large scales, including the enactment of large marine protected areas and other conservation policies or fisheries regulations around the world. Sustainable use of marine resources must be incentivized regardless of alternative industries, and tourism can never fulfill all of the potential benefits of, for example, a sustainable fishery. Yet, the economic and ecological benefits of ecotourism, and their subsequent social and political effects, will be increasingly prevalent at both local and larger spatial scales.

Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, Vicky Lam, Gabriel Reygondeau, Wilf Swartz, Yoshitaka Ota – “Links between human conflict and marine ecosystem health”

Abstract: The environmental and social impacts of climate change will be increasingly difficult to mitigate and adapt to, and instances of environmental shocks triggering human crises have been observed around the world. Coastal communities are particularly vulnerable to the negative environmental and social outcomes of ongoing global change, due to mostly open-access conditions in marine regions. We present a conceptual model linking vulnerability to resource scarcity and human governance, and support this framework using global data. Our results show a direct relationship between national-scale governance and marine ecosystem status, where areas with poor governance and poor ecosystem health show increased instances and severity of human conflicts. These findings have significant implications for regions where local anthropogenic pressures and climate change are expected to lead to further stress on marine ecosystems, and subsequent higher risk of environmentally-triggered human conflict.

Monday, August 1, 2016

The impact of overfishing and climate change on food security and human nutrition – 11:00-13:00

Vicky Lam, William Cheung, Rashid Sumaila, Gabriel Reygondeau, Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, Wilf Swartz – “Future projections of global and regional marine fisheries catches” – 11:15

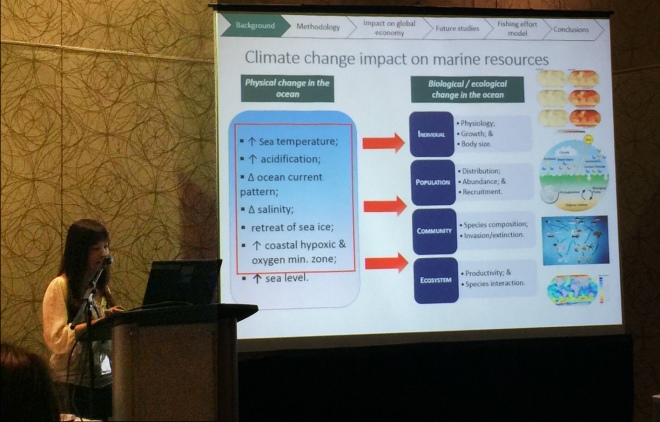

Abstract: Impacts of climate change on the distribution range, biomass, the physiology and eventually the catch potential of marine species have large implications for the people who depend on fish for food and income, and thus economics of society as a whole. In our previous studies, we combined the outputs from dynamic bioclimate envelope models (DBEM) with the economic parameters to project the impact on the revenues and the ripple effects of the whole economy of each of 192 fishing nations. Also, we applied this model to project the potential impacts of climate change on the economics, food and nutritional security in some climate vulnerable regions such as the Artic and West Africa. However, the previous version of DBEM does not include the routine on modeling how the catch amount and profit affecting the investment and ultimately the fishing effort. Meanwhile, there is no feedback pathway for the effect of dynamic changes in effort on biomass and catches. To address these, we incorporate the fishing fleet dynamics by combining a simple bioeconomic model, which assumes active effort will seek to maximize profits from a fishery given yearly price and cost information, with the DBEM. These profit maximizing vessels will choose whether to enter a fishery or remain in the dock in the next year based on profitability of the fishery. This presentation will explain this framework and its implications in our future climate change impact analysis.

Vicky Lam – “From marine ecosystem transformation to human nutritional outcomes: insights from Bangladesh” – 11:45

Abstract: Momentum for policymaking around marine conservation depends on rigorously quantified estimates of the impact of ecosystem transformation on human well-being. The scientific challenge is to develop methods for robust inference across the long, complex causal chain from ecosystem structure to health outcomes. Using data from Bangladesh, we present a workflow for integrating three independent models: 1) an ecological model to project changes in abundance and distribution of marine species in response to climate change and fisheries management; 2) a multi-market economic model to derive equilibrium states in fisheries production, consumption, and trade; and 3) a nutritional epidemiology model that predicts the consequences of changes in consumption of fish products on specific health conditions. We assess how various scenarios of marine ecosystem transformation affect the evolution of health status in Bangladesh between the present day and 2050, disaggregating results by rural inland, rural coastal, and urban populations in the country.

Lauren Weatherdon, Yoshitaka Ota, Miranda Jones, William Cheung – “Projected scenarios for coastal First Nations’ fisheries catch potential under climate change: implications for management and food security” – 12:00

Abstract: Studies have demonstrated ways in which climate-related shifts in the distributions and relative abundances of marine species are expected to alter the dynamics and catch potential of global fisheries. While these studies assess impacts on large-scale commercial fisheries, few efforts have been made to quantitatively project impacts on small-scale subsistence and commercial fisheries that are economically, socially and culturally important to many coastal communities. This study uses a dynamic bioclimate envelope model to project scenarios of climate-related changes in the relative abundance and distribution of 98 exploited marine fishes and invertebrates of commercial, nutritional, and cultural importance to First Nations in coastal British Columbia, Canada. Declines in abundance are projected for most of the sampled species under both the lower and higher emissions scenarios (-15.0% to -20.8%, respectively), with poleward range shifts occurring at a median rate of 10.3 to 18.0 km per decade by 2050 relative to 2000. While a cumulative decline in catch potential is projected coastwide (-4.5 to -10.7%), estimates suggest a strong positive correlation between the change in relative catch potential and latitude, with First Nations’ territories along the northern and central coasts of British Columbia likely to experience less severe declines than those to the south. These results are discussed in light of associated management challenges and impacts on food security.

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Fisheries, aquaculture and the oceans 8 – 8:30-10:30

Daniel Dunn, Guillermo Ortuño Crespo – “A review of the impacts of fisheries on open-ocean ecosystems” – 8:45

Abstract: Pelagic environments are the most widespread type of ecosystem on Earth, covering twice the surface area of all other terrestrial systems combined, and orders of magnitude more volume. The dynamism of these three dimensional systems makes them very complicated to define in space and time, and even more difficult to monitor for potential ecosystem impacts of anthropogenic stressors. Our capacity to exploit these systems far exceeds our ability to gauge the impacts of that exploitation, particularly in areas that lie beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ). Against this backdrop, the United Nations passed a resolution to begin negotiations on a new mechanism to allow for the sustainable use of biodiversity in ABNJ. Here, to inform the discussion of whether or not fisheries should be excluded from the new agreement, we review recent literature to identify evidence for, and trends in, the impacts of fisheries on pelagic populations, communities and ecosystems. Such impacts include directed fishing mortality of target species or bycatch. The collateral effects of these impacts include: alterations in the range and demographics of populations, changes in the composition and trophic stability of ecological communities or loss of species and biodiversity. Given the migratory nature of many of the species which comprise these communities, ensuring the health and integrity of oceanic ecosystems, will have a positive repercussions in both open ocean and coastal fisheries and ecosystems.

Conserving the other 50% of the world: Status and opportunities in area-based management beyond national jurisdiction – 08:30 – 10:30

Patrick Halpin – “Results, implications and future directions of the first intergovernmentally sanctioned effort to describe ecological or biologically significant areas (EBSAs)” – 9:00

Abstract: Over the last several years the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity has been organizing a series of regional efforts to describe ecologically or biologically significant areas (EBSAs) in both national exclusive economic zones (EEZs) as well as areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ). These regional efforts have now covered the majority of the global oceans so it is now an especially important time to take stock of the current distribution of EBSAs described to date and to examine future directions in this process. There are a number of questions that are emerging as we take stock of the process. These questions include: how have EBSAs described to date captured different types of marine features, habitats and categories of species? What are the implications of EBSA descriptions for migratory marine species? How can we better categorize EBSAs into more specific categories (fixed features, aggregated features, ephemeral features and dynamic features)? What can be done to better refine and communicate the results and necessary caveats of the EBSA process to decision makers? How can the international community potentially refine individual EBSA descriptions and regional workshop outcomes? Answering these types of questions have been the topics of recent international expert meetings and will help to guide the future development of the EBSA process. This presentation will provide an current update on the EBSA process and implications for future activities.

Daniel Dunn – “The call for MPAs in areas beyond national jurisdiction: identifying real needs and false assumptions” – 9:30

Abstract: The Convention on Biological Diversity’s Ecologically or Biologically Significant Area process and the UNGA’s Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Working Group have focused attention on the need for area-based conservation measures in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ). This has led to an increase in calls for the use of marine protected areas in the open-ocean and deep seas; generating a strong need to understand how studies of coastal MPAs can be transferred to ABNJ waters. In this presentation, we examine threats to biodiversity in ABNJ and consider how they have been reduced in coastal zones through the use of protected areas. In enumerating the scope of potential uses of MPAs in coastal zones, we identify gaps in how MPAs are being employed in ABNJ. We highlight the importance of objectives unrelated to resource extraction and question what existing institutions might ensure such cultural, scientific and conservation objectives are considered in ABNJ. Further, we look at the potential benefits derived from MPAs in coastal areas and examine evidence of their transferability to the open-ocean and deep seas. Of particular interest is how concepts of habitat and representativity may be applied in the pelagic realm and the degree to which we can expect traditional fisheries benefits from MPAs (spillover, larval export, etc.) to accrue in these zones. We also consider the transferability of other area-based management measures (e.g., dynamic ocean management).

Daniel Dunn – “Conserving the other 50% of the world: status and opportunities in area-based management beyond national jurisdiction” – 9:45

Abstract: Areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) in the word ocean covers over half of Earth’s surface and encompasses significant portions of the world’s open ocean and deep seas. Although the oceans have been utilized by humans for millennia, it is only recently that a significant increase in human activities in the open oceans and deep seas is being observed, increasingly threatening marine biodiversity. Adding to this, are indirect effects caused by global climate change, putting additional pressure on these ecosystems. This has led to repeated calls for the conservation of ABNJ. However, no comprehensive mechanism exist as yet to conserve its biodiversity but recently the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution to establish a Preparatory Committee to begin negotiations on a new legally-binding instrument for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in ABNJ. The negotiations will set the stage for the conservation of biodiversity for the other 50% of the planet and represent an enormous opportunity to inform conservation policy and effect change. In this talk we will present the main findings of the workshop that examined the status and opportunities for conservation of ABNJ by reviewing new scientific findings and current sectoral efforts to conserve biodiversity. We will make a synthesis of the discussions held and examine how it can inform the new legally-binding instrument for the conservation and sustainable use in ABNJ.

Fisheries, aquaculture and the oceans – 11:00-13:00

Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, William Cheung – “Evaluating biodiversity targets in marine ecosystems: a fuzzy logic framework” – 11:15

Abstract: The Aichi Biodiversity Targets were developed by the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and its member parties to support global conservation and sustainability efforts. They are divided into twenty concrete Targets within five Strategic Goals, with most targets intended to be reached by the year 2020. However, evaluating progress can be difficult given that targets focus on desired outcomes rather than specific measurable benchmarks. Therefore, we developed a fuzzy logic system that evaluates overall progress based on sets of indicators corresponding to each target. A key aspect of this method is that all assumptions are transparent and can be easily modified to gauge their impact on results. We apply this method to evaluate progress specific to Canadian marine ecosystems, though the framework is designed for application to any problem where data is spotty and/or progress is difficult to measure.

Full list of presenters

WILF SWARTZ, PHD, FISHERIES ECONOMICS

WILF SWARTZ, PHD, FISHERIES ECONOMICS