A new Nereus Program study, funded by the Nippon Foundation, finds that dynamic ocean management, which changes in real time in response to the nature of the ocean and its users, can reduce bycatch — fish and marine species caught accidentally while catching targeted species — without additional costs to fishers.

“For a while, the speed of communications between fishermen and managers was outpaced by the speed at which fishermen could catch fish and impact the ecosystem,” said Daniel Dunn, Nereus Fellow at Duke University and lead author of the study. “But now, fishermen and managers can communicate catch data with each other using mobile apps such as eCatch, Digital Deck and Deckhand, or even just emails or texts. It is a real game changer.”

The study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), and co-authored by Nereus Principal Investigator Patrick Halpin and Nereus Alumnus Andre Boustany, states that dynamic ocean management may be able to make fisheries more sustainable, from ecological, economic and social standpoints.

The study authors found that small-scale, real-time management increases the efficiency and efficacy of fisheries. Image: “Fleet at Rest” by Savannah Sam Photography, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

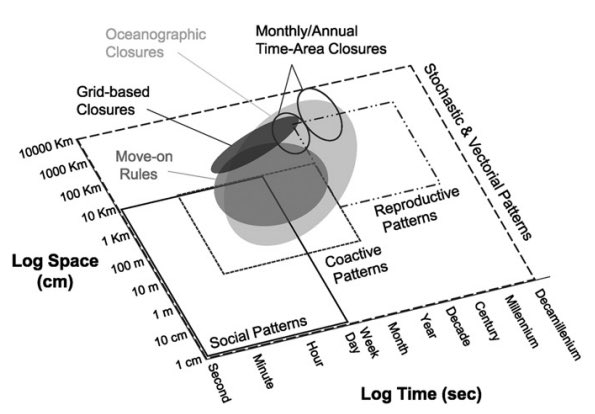

Looking at six types of fishery closures, they found that small-scale, real-time management increases the efficiency and efficacy of the fisheries. Dynamic closures of smaller portions of the ocean, making them off-limits for fishing for shorter periods of time based on current ocean conditions, are up to three times more efficient at reducing bycatch.

“The most basic implication is that we could be managing fisheries more efficiently and reducing the burden on fishermen in terms of the times and areas they are allowed to fish in while actually increasing the conservation benefit, for example, by reducing bycatch,” said Dunn.

The authors found that this type of dynamic ocean management can reduce bycatch when fishing more mobile species, like bluefin tuna, as well as bottom-dwelling species like scallops.

“On a basic level, we need to work with fisheries managers to make sure that they are managing on a scale relevant to the process driving the ecological problems they are encountering and not just on a scale that is hopefully relevant to one target population,” said Dunn.

Fig. 2. Spatiotemporal scales of Hutchinson’s five patterns and fishery management measures. Traditional spatiotemporal fisheries management measures (i.e., monthly and annual time–area closures) can only address reproductive and some vectorial patterns at appropriate scales. However, dynamic management measures (i.e., closures based on oceanography, grid-based hotspot closures, and real-time closures based on move-on rules) should be able to address social and coactive patterns as well as some vectorial and reproductive patterns.

For further information or interview requests, please contact:

Lindsay Lafreniere

Communications Officer, Nereus Program

Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries

The University of British Columbia

[email protected]