You’ve seen the headlines – tuna is in trouble. “Bleak outlook for sushi favourite as bluefin tuna levels drop 97 per cent,” writes the Telegraph. CBS News says: “Sushi eaters pushing Pacific bluefin tuna to brink of extinction”. Does this mean that you should be putting down those tuna sandwiches and spicy tuna rolls? Not necessarily.

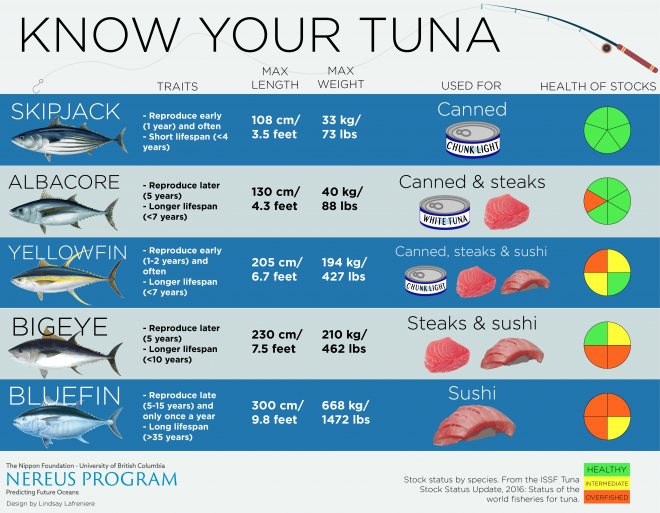

When considering whether or not to eat tuna, it’s important to look at both the health of the fish stocks and the ecosystem effects of the tuna you’re buying. There are five major types of commercially important tuna – skipjack, albacore, yellowfin, bigeye, and bluefin. Each type has a different taste and texture and is used for different food items for humans and animals, from poké to cat food. According to the 2016 ISSF Tuna Stock Status Update, 52% of the global stocks are a healthy level, 31% are overfished, and 17% are at an intermediate level. Some stocks are in more trouble that others, especially bluefin.

“Pacific bluefin are still being overfished, they’re not doing well. But, for the most part, things are much better than they were ten years ago for most of the bluefin species,” said Andre Boustany, Nereus Program Principal Investigator at Monterey Bay Aquarium and 2011-2013 Fellow. Boustany has done extensive research on tuna and is a member of the Advisory Committee to the U.S. Section to the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). “Atlantic bluefin is doing much better. They’ve still not recovered, but we have ended overfishing.”

The skipjack stocks are healthy and sustainable, as well as many of the albacore. Yellowfin and bigeye tuna are somewhere in the middle. (See figure “Know your Tuna”.) While bluefin tuna is currently unsustainable, most people are not exposed to it as the majority is eaten in Japan as sushi.

“More often than not, if you’re eating tuna sushi in a restaurant in North America, it’s yellowfin or sometimes bigeye. Bluefin has a richer flavour,” said Boustany. “In the US anyway, people want less flavourful fish so they actually prefer yellowfin. Yellowfin doesn’t have the fatty cuts because it’s a lot leaner. That’s why there’s a premium for bluefin — it’s a fattier, oilier fish, and more flavourful.”

The health of tuna stocks depends on how many of the fish are being pulled from the ocean, but it also depends on the traits of each species. Skipjack tuna are smaller, but reproduce quickly and often, reaching sexual maturity at one year old. Whereas bluefin species don’t reproduce until they are five to fifteen years old and even then, it’s only once a year. Skipjack are able to replenish their populations much faster than bluefin and better withstand fishing pressures.

While bluefin stocks are the most in trouble, the majority of it is eaten in high end sushi restaurants in Japan and around the world. Image by Lindsay Lafreniere.

The issue of bycatch

While some tuna stocks are sustainable, on the downside, the ecosystem effects can be very damaging. Bycatch is the fish, birds and marine mammals that are caught, injured, and often killed in the process of fishing a targeted commercial species. In the case of tuna, this includes turtles, seabirds, dolphins, and other fish.

“It’s pretty bad with skipjack and yellowfin especially in the Eastern Atlantic, the Gulf of Guinea, and the Western Central Pacific. In these places, they use fish aggregating devices,” said Boustany. “They’re catching a lot of sharks, rays, and turtles, as well as a lot of juvenile bigeye tuna. This has been impacting the ability of the bigeye stock to recover as they’re being caught in fisheries targeting skipjack and yellowfin.”

Fish aggregating devices have been used for hundreds to thousands of years, since fishers first noticed that tuna naturally gather under logs and other floating materials. The devices work by using artificial floating objects attached to large nets called a purse seine that encircle an area of the ocean and then scoop up large amounts of tuna and other marine species as bycatch. Purse seines are used in 64% of tuna fishing. Longline fishing, with a main line of up to 150 km with smaller lines and baited hooks, is used in 12% of tuna fisheries. Longlines have a similar issue with bycatch as sea turtles, birds and sharks will often get caught eating the baited hooks. Pole-and-line caught tuna makes up about 9% of the market, but has little to no bycatch.

“When I’m going to eat any canned or prepared tuna, I’ll eat pole-and-line caught albacore. In a restaurant, I’ll try to find out where it’s from, whether it’s local or not, and how it was caught. In most of the areas where I’ve lived, that has been possible, just because there’s been a consciousness about sourcing fish responsibly,” said Boustany. “Yellowfin and albacore are pretty good choices, but there are some bycatch issues with each of those. Try to do what you can when buying a steak or sushi in a restaurant. Try to find out the source. If they know, they’ve probably sourced it in a way that’s better than average.”

Bluefin tuna are remarkable fish, they can swim up to 70 kms per hour and cross the ocean in 21 days. Image “Tuna” by Vlad Karpinskiy, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The future of tuna

With climate change, marine species are expected to move towards cooler areas, generally closer to the poles and into deeper waters. Boustany has already seen changes in the distribution patterns of some tuna species, but it’s less of a concern with these very mobile fish.

“If their prey shifts or if oceanographic conditions shift from one area to another, tuna are going to be able to adapt pretty easily because they can swim across the ocean in 30 days,” said Boustany. “Where it may have a bigger impact is in the spawning areas, which are generally in more tropical areas. If the spawning areas become less suitable, you can get big differences in the reproductive output per adult. The tropical tunas like skipjack and yellowfin live in the same place as they spawn, so they spawn year round. Bluefin are feeding up in sub polar latitudes and swim back to the tropics in order to spawn.”

And since there is such a demand for tuna, should we be looking for alternative sources? Tuna has been farmed, but Boustany believes that this won’t benefit the wild stocks.

“It’s always going to be more expensive to raise a tuna completely in captivity to market size then it is to go out and catch it. Another issue is that, when we’ve been successful raising fish, we thought it would decrease fishing pressures on wild populations and that has not borne out,” said Boustany. “What it does is create additional markets so you may be actually popularizing a fish that was a premium product before and now is a mass product. The fishing pressure still stays there — it’s not the great saviour that a lot of people pretend it to be.”

For further information or interview requests, please contact:

Lindsay Lafreniere

Communications Officer, Nereus Program

Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries

The University of British Columbia

[email protected]