When you find a fish at a decent price, there’s more than meets the eye. Behind that price tag lies a whole supply chain that remains untraceable and unseen to the average consumer, which can create the illusion of sustainable practices.

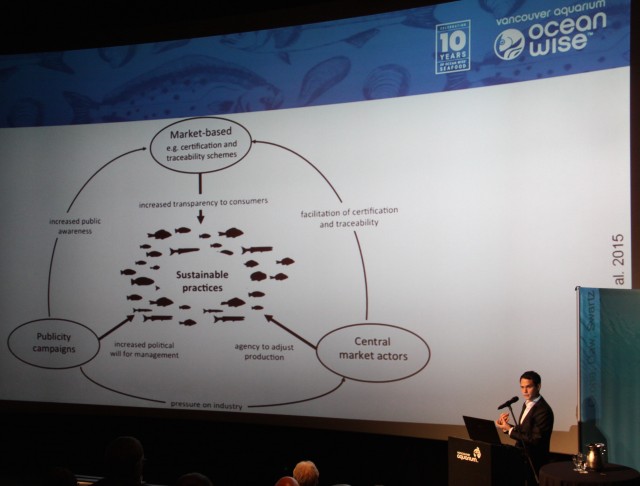

Wilf Swartz, Research Associate with the Nereus Program, is calling for a more transparent system— as well as increased public awareness and corporate social responsibility surrounding sustainability.

In a new paper published in Fish and Fisheries, “Masked, diluted and drowned out: how global seafood trade weakens signals from marine ecosystems,” Swartz and colleagues argue that market price isn’t the right signal for sustainability. There’s actually a whole lot more going on behind the scenes, he states, and that information needs to be made more visible.

“There’s a disconnect between what’s going on in the ocean and what we see in the market,” Swartz says.

Wilf Swartz presents at the Ocean Wise Seafood Symposium on April 27, 2015.

(Image courtesy of Meighan Makarchuk, Vancouver Aquarium)

With consumer appetite for seafood on the rise, market demand often places pressure on particular popular fisheries and—unfortunately—fish stocks gets overexploited. This means that it becomes much harder to catch the fish as there are less of them, which results in fishers spending more time at sea searching for fish to catch.

In theory, this process should drive up the cost of fishing. But the consumer never actually sees the price change reflected in the product. Swartz points to our globalized society and use of technology for an answer.

“Even though the [fish] stock size is going down, [it’s] because we are continuously improving our technology [that it’s] getting easier to catch the fish,” he says.

At the same time, fisheries are expanding. With more options available, consumers may be unaware that overexploitation is a real concern. If one stock is going down, there is easy access to another stock, or the potential to supplement it with aquaculture or a different species.

As a result, the perception of value gets skewed.

“The consumer doesn’t see that the fish are being overexploited and disappearing,” Swartz says. “And we argue that that’s not a good thing because, as a consumer, you’re constantly being told that the problem with the ocean is that there’s exploitation, there’s climate change—all of these things are happening and we need to do something about the ocean.”

But when a consumer goes to the grocery store, he explains, the variety in seafood is still there and the price is still reasonable.

“So what we hear and what we see is not matching up and that’s creating an illusion of healthy fish stocks to the consumer. They say, ‘Well, you know, maybe overfishing is happening somewhere but it’s not happening to what I’m eating because the price for this fish is still not increasing.’”

In the paper, Swartz and colleagues suggest that fish price as a feedback signal to consumers about the state of fisheries and marine ecosystems needs to be improved. Right now, the current system involving fisheries and global markets prevents the transmission of price signals from the source to consumers—and that’s a challenge for sustainable fisheries governance.

In particular, Swartz and colleagues looked at the example of North Sea cod in the U.K. to address the weaknesses in price feedback. Even though the population size of North Sea cod went down, the price — which was the only thing seen by consumers– was unresponsive to this decline. The authors then proposed three main approaches to bridge this gap:

- Strengthen information flow through improved product traceability to consumers,

- Provide consumers with knowledge of the state of the ocean through direct public campaigns,

- Restructure the business models of seafood supply chains, targeting key firms.

Swartz has taken these ideas further with his current research on seafood supply chains and corporate social responsibility of many global seafood firms. He recently had the opportunity to present this work at Ocean Wise’s Tenth Anniversary Seafood Symposium in Vancouver on April 27.

“My main argument is that usually when we talk about fisheries sustainability and seafood industry behaviour we typically look at these as two isolated issues,” he says. “People tend to study fishers and consumers or specific company business practices, and so you don’t see the interaction between these groups.”

In order to map that interaction, Swartz turned to the idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR)—the philosophy that a company should go beyond typical expectations and integrate environmental initiatives into their business. He’s building a database that looks at 150 seafood companies, their profiles, and their policies on corporate responsibility.

“I think meaningful sustainability objectives can be well-integrated into viable business strategies. That said, when it comes to CSR, the seafood industry is clearly lagging behind other natural resource industries like forestry and mining.” In this regard, Swartz hopes that his work will identify key trends and causes of this disparity.

As well, Swartz notes that the private sector can’t advocate for more sustainable practices alone. Government action must be a prominent factor in policy change.

“We can’t just pass on that responsibility to the private sector,” he says. “The government needs to be there, but they would benefit from gaining a better understanding of what private initiatives are out there. It allows the government to be more strategic about how to implement effective policies.”

When it comes to public awareness, Swartz cites ecolabels such as Ocean Wise as one effective example of communicating with the public.

“I think that consumer-facing programs like Ocean Wise are filling the need for better, improved transparency down the supply chain and I totally support that,” he says.

But at the heart of Swartz’s message is for business to build relationships with local communities first.

“Especially in fishing or aquaculture, you operate in a certain area and you need to get the support of the local community,” he says. “In commerce we call it social license: the idea that we get a license to do business from a society.”

For Swartz, being part of Ocean Wise’s tenth anniversary was an honour, giving him the chance to speak and collaborate with local business people who can affect real change.

“I got into some interesting conversations with local seafood suppliers and restaurants,” he says. “And I’m looking forward to where this is going.”

By Emily Fister