In our current eco-friendly world, where climate change makes front-page news and the killing of a lion launches thousands of Facebook posts, how can a porpoise be nearing extinction and most of the world not even know of its existence?

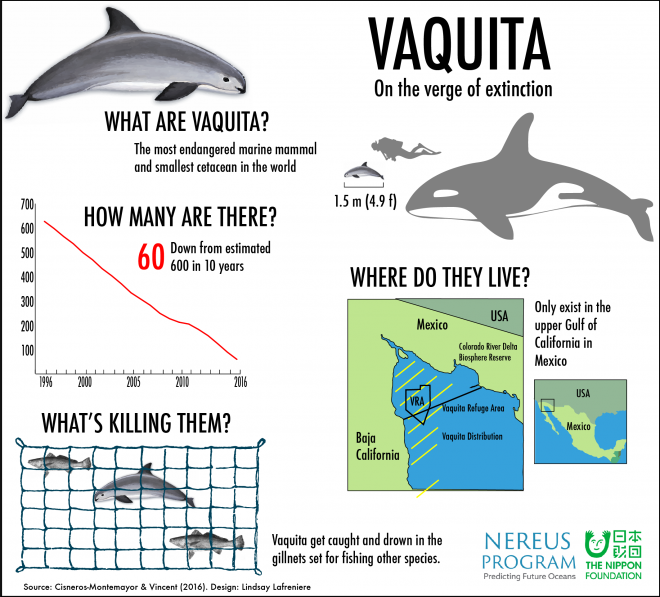

The vaquita is going extinct at an alarming rate, from an estimated 600 individuals in 1996 to 60 in 2016, states a report presented to Mexico’s Minister of the Environment and Natural Resources earlier this month. It’s the world’s smallest marine mammal, with a maximum length of only 1.5 meters (4.9 feet). And with its dark eye patches and mouth that seems to curl up into a smile even after death, the vaquita is not missing out on the cute factor.

“Some call it the Mexican panda,” says Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, Nereus Program Fellow at UBC, who recently published a paper discussing the vaquita and totoaba as flagship conservation species in the Gulf of California. “The vaquita is a very big conservation problem. Overfishing is bad for any species but this is an iconic marine mammal. If there’s anything you should be conserving, it’s this guy.”

Not much is known about the world’s most endangered marine mammal, which wasn’t described by scientists until 1958. It’s rarely seen even by the fishermen that sail local waters. Acoustic and visual surveying were used to identify the sound of the little creature and determine its population.

The first vaquita to be photographed. Image: Alejandro Robles

The vaquita lives in just one area in the world – the upper Gulf of California, the area in Mexico between the western Baja California Peninsula and the mainland. This area includes traditional fishing grounds for Indigenous groups and other commercial fisheries. Most deaths of the vaquita are attributed to them being caught and drowned in gill nets that are set for fish and shellfish in the gulf.

The vaquita’s story is closely tied to that of another endangered species – the totoaba. The totoaba fishery collapsed after reaching catch levels of more than 2,000 metric tons in 1942. In 1976, the totoaba became the first fish to be listed as endangered, and subsequently all fishing of it was banned. Unfortunately, illegal fishing continued as catching one is incredibly lucrative. Today, the swim bladders of totoaba can be sold in China for as much as $10,000 per kilogram.

“The original idea to protect the upper Gulf of California came from overfishing of the totoaba. Back in the day, totoaba was a very important fishery and then it just collapsed,” says Cisneros-Montemayor. “The USA put dams on the Colorado River, like the Hoover Dam that formed Lake Mead. There was no more water flowing into Mexico and that whole habitat was destroyed. There was overfishing for sure, but that loss of habitat also contributed to the totoaba decline.”

The area where both the totoaba and vaquita reside is part of the Colorado River Delta Biosphere Reserve, an area that has drastically changed over the past 80 years due to dam constructions and water diversions.

“The delta that used to be there was a very productive and very unique ecosystem within the Gulf of California,” says Cisneros-Montemayor. “This used to be forest, but now it’s mostly desert. There’s not much you can do to return these species to their historical population numbers without bringing back this ecosystem. It’s not just the fishing that’s the cause.”

And why fishing has been killing the vaquita is also part of a wider social problem.

“We need a much more concerted effort to tackle the underlying causes of overfishing. Often that’s poverty, not always, but it does play a big role. People need to fish because they need to provide for their families,” says Cisneros-Montemayor. “The people who live in these communities have zero incentive for conservation. For these communities, fishing is the only thing that they can do. A lot of these communities have just been forgotten. They’re out in the middle of nowhere, there’s one road, and there are no other opportunities except for this.”

Cisneros-Montemayor notes that there are few other industries or alternative ways to make a living in these small communities, with many people ending up going to the USA or turning to work in drug cartels. And while tourism has allowed a lot of money to flow into other areas of Mexico, that also requires a lot of infrastructure and previous knowledge.

“It’s a problem that can’t be solved through ecology or conservation; it’s a much wider problem. What should have been done 100 years ago is really invest in other opportunities for these people,” says Cisneros-Montemayor. “The problem in this particular case, and throughout the world really, is that instead of creating other jobs that are going to lift people out of poverty or investing in infrastructure, formal education and industries, fishing is seen as an easy out for governments. We need to focus on ways to get people to self manage the resource and believe that sustainability is bringing them a personal benefit.”

For further information or interview requests, please contact:

Lindsay Lafreniere

Communications Officer, Nereus Program

Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries

The University of British Columbia

[email protected]