By Colin Thackray, Nereus Fellow at Harvard University

The oceans are very expansive. Their enormous size and distance from where people stay long term presents a challenge for scientists monitoring the oceans. Unlike many atmospheric measurements for meteorology which we can make just outside of cities, often at airports, to get good measurements for ocean science, a journey on the sea is often required. Around the world, there are many ships designed or outfitted specifically for bringing scientists to the ocean – so called Research Vessels (RVs).

In the United States, the National Science Foundation owns and supports a few RVs, one of which is RV Endeavor which is operated by the University of Rhode Island, and has a home port in Narragansett. The Endeavor spends more than half the year at sea with science parties conducting physical, chemical, and biological ocean research. This 185-foot vessel is specially outfitted for ocean science, and has carried scientists all across the Atlantic Ocean, from north of the Arctic circle to South America. Oceanographic research on any given cruise that the Endeavor undertakes often spans many specific fields of study, with physical oceanographers working alongside biologists and chemists, and also gives graduate students a chance to experience and perform hands-on oceanography.

RV Endeavor brings scientists from many fields onto the oceans. Photo courtesy of Miling Li.

My field of study is environmental pollution caused by persistent toxic substances, such as mercury, which are emitted by human activity and remain in the atmosphere, ocean, and/or biosphere for long periods of time. For many substances like this, the kinds of measurements that can be made on RVs such as the Endeavor are vital to our understanding of how they behave in the environment.

In April, as part of the science party on the Endeavor, my goal was to collect seawater samples to be returned to our laboratory to measure their mercury content. Mercury gets into the ocean mostly through the atmosphere when it rains and through river outflow. It can get into these environments by burning coal or by mercury amalgam-based small scale gold mining, which is about 20% of all gold mining. Mercury can be converted into a toxic substance called methylmercury in the oceans, which bio-magnifies up the food chain. Methylmercury causes adverse health effects to both marine organisms and the people that eat them. It has been linked to reproductive, growth, and behavior impairment in fish and wildlife, and developmental deficits and cardiovascular disease in humans.

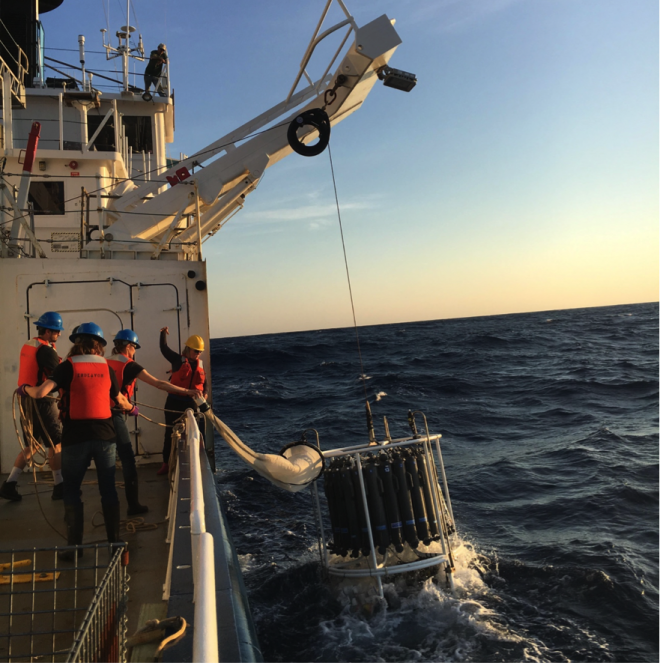

An important piece of information to know about mercury in the ocean is how its concentration changes from the ocean’s surface to greater depths. To get this information, we use a sampling device (pictured below) on a winch that we lower over the side of the ship. With thousands of meters of cable, this device can be lowered deep into the ocean. At depths of our choosing, we can close bottles attached to it using a remote control, trapping seawater from those depths. When this collection process is finished, the device is brought back on board and the seawater is transferred from the sampling device to transportable bottles to be returned to our lab after the cruise ends, where their mercury content can be measured.

Using a sampling device on the ship allows us to measure not only mercury levels in the ocean, but levels in the atmosphere in the past. Photo courtesy of Ali Johnson.

By performing these measurements, we can get insight into not only the current state of mercury in the ocean, but some history as well. The very deep waters of the Atlantic have not been exposed directly to the atmosphere in many years, and knowing how much mercury is down there tells us about how much mercury was in the atmosphere in the past, as well as how mercury cycles through different parts of the environment. Performing these measurements far from the human sources of emissions also tells us about how long toxic substances such as mercury last in the environment.

While the Endeavor and other RVs perform important research functions, they are also used as tools for education. While I was aboard, there were a handful of students from different New England graduate oceanography programs getting the hands-on experience that will allow them to become influential researchers in their fields. We were accompanied by a school teacher who was able to show her class the ship via video while on board, and bring back material and knowledge to hopefully spark their interest in the oceans and science. Sometimes research cruises can also help to reinforce our appreciation of the parts of the ocean that everybody wants to maintain (pictured below).

Photo courtesy of Ali Johnson.

COLIN THACKRAY, PHD, ATMOSPHERIC CHEMISTRY

COLIN THACKRAY, PHD, ATMOSPHERIC CHEMISTRY

Harvard University

Colin Thackray is a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University, with a background in numerical modeling of atmospheric physics and chemistry. He is developing a modeling framework to trace anthropogenic emissions (to the atmosphere and oceans) of toxicants such as mercury through the physical environment into marine food webs to assess the toxicants’ effects on fisheries health and sustainability. This framework will also help project future fisheries sustainability under changing fishing/climate/emissions.