“After climate change, fishing is the biggest impact humans will have on the oceans. But we have a very limited understanding of what happens beyond the horizon. It’s out of sight,” says David Kroodsma, Global Fishing Watch Research Program Manager at SkyTruth. “Global Fishing Watch allows us to see where the fishing is happening and how much. This will lead to whole hosts of answers to questions about how we manage our oceans.”

With Global Fishing Watch, we can now see beyond the horizon. A collaboration between SkyTruth, Google, and Oceana launched in mid September, it’s a publicly available platform that uses satellite data to track fishing boats around the world. Kroodsma will be discussing the project at a Nereus Program seminar held at the University of British Columbia’s Green College on October 27. This seminar is free and open to the public.

Global Fishing Watch uses Automatic Identification System (AIS) data – a system originally developed to prevent collisions at sea. Boats use AIS to broadcast information about who they are and what they’re doing; the messages can include information about the name of the ship, identification numbers, position, speed, and course.

“If you have your own boat, you may see there’s a tanker ten miles ahead and which way it’s going, so you can make sure you don’t collide. These signals are broadcasted everywhere and are picked up by satellites,” says Kroodsma. “You can also broadcast which port you’re going to and what type of vessel you are, such as a fishing boat, tanker, passenger vessel, or sailing ship.”

Global fishing activity over three months, from July to October 2016. Screenshot from: Global Fishing Watch.

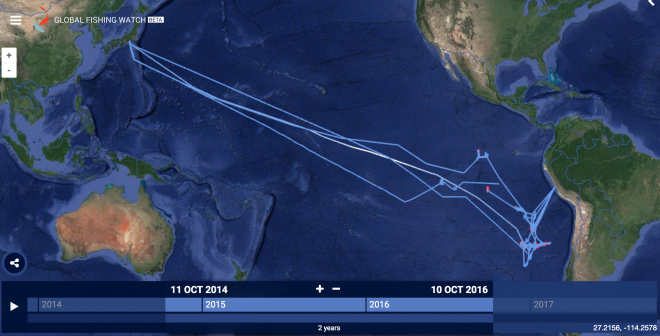

Global Fishing Watch is essentially like Google Maps for the oceans. The timescale shows segments of time, from days to years, back to 2012. Fishing activity shows up as yellow dots. Hovering over a cluster of dots shows connected lines – the track of a fishing boat. Clicking on that track brings up information of the vessel – such as name, identifications, and flag. The map also shows marine protected areas and exclusive economic zones and can be filtered by country. For example, it’s possible to see the track of a boat leaving from Shizuoka, Japan, named Kaio Maru No. 81 cross the Pacific, fish off South America and go to port in Lima, Peru a few times.

Kroodsma notes that a challenge is that AIS information is self-entered by the user, so there can be mistakes or missing data. The AIS system can also be turned off but Global Fishing Watch can highlight this as suspicious behaviour. Turning off AIS can also lead to questions about whether that boat should continued to be insured.

Global Fishing Watch is the first time that this data has been used to get a scale of global fishing efforts.

“We’re working with people like Nereus Program researchers to answer the question of: how do we use this huge database of the way boats are moving to say something about fishing activity?” says Kroodsma. “If you know exactly how it’s moving and the size of the boat, you can say meaningful things about how much it costs to operate that boat and how much the trip costs. We can look at the cost of operation and figure out how much fish they’d have to catch to make it viable.”

Global Fishing Watch can be used to track fishing vessels from certain countries, such as this ship called Kaio Maru No. 81, from Japan. Screenshot from: Global Fishing Watch.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing could also be spotted with this tool. This is essential information since 30% of global fish catches goes unreported, according to Sea Around Us, a Nereus Program collaborator. Without accurate information about fish catches, it’s difficult to understand the state of oceans and fisheries.

“Global Fishing Watch will be able to help us identify the unregulated or the under recorded parts of the oceans; help us know where there’s overfishing based on how many boats we see,” says Kroodsma. “We’re also working on identifying shipment trends, which is a large source of IUU. Large fish carrier vessels go out to sea, the fishing boats unload the catch onto them, and then they go back to port. This is a way for fishing boats to avoid dealing with regulations since it’s no longer clear exactly where the fish are coming from. We can use AIS data to track the carrier vessels and see which other boats they’re meeting up with.”

There are a few commercial companies that provide AIS data. SkyTruth buys the data and then processes it; their goal is to make as much of our data freely available as possible. They’re also curating lists of fishing vessels from different sources, such as individual countries and regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs), to match up information and have a more complete database.

“We’re at an exciting point because Global Fishing Watch is really a confluence of a number of different factors – with the arrival of big data computing infrastructure, we now have the ability to process billions of data points in a way that we did not a few years ago, and also satellite technology has advanced,” says Kroodsma. “These new satellites are cheaper and there’s more of them. The last piece is having an organization, such as Global Fishing Watch, that is able to process this vast amount of information and make it available. This is something that’s only been possible at this scale in the last two to three years.”

Learn more about how big data can aid fisheries management when David Kroodsma speaks at UBC’s Green College on October 27.

More about David Kroodsma: David has over a decade of experience researching and communicating global environmental issues. Trained in physics (BS) and earth systems science (MS) at Stanford University, he has worked with several nonprofits and foundations as a researcher, consultant, and data journalist, all with the aim of addressing global environmental challenges. A long distance cyclist, he has also used continent-crossing bicycle journeys to draw attention to climate change through his Ride for Climate project, and he is the author of The Bicycle Diaries, a Shelf Unbound Notable Book of 2014 and a finalist for both the Montaigne Medal and Forward Review’s IndieFab Book of the Year. He lives in Oakland, California.

More about David Kroodsma: David has over a decade of experience researching and communicating global environmental issues. Trained in physics (BS) and earth systems science (MS) at Stanford University, he has worked with several nonprofits and foundations as a researcher, consultant, and data journalist, all with the aim of addressing global environmental challenges. A long distance cyclist, he has also used continent-crossing bicycle journeys to draw attention to climate change through his Ride for Climate project, and he is the author of The Bicycle Diaries, a Shelf Unbound Notable Book of 2014 and a finalist for both the Montaigne Medal and Forward Review’s IndieFab Book of the Year. He lives in Oakland, California.